Where the waters meet

The great necropolis in the west

Lights rise from it at night. So the miners said, dragging their weary way across Ballowall Common, candle hats streaked with wax. After ten hours labouring in the dark, following the seams of tin out under the treacherous sea they had to pass by Carn Gluze to get back to town. Strong beer awaited, and a cot in their cramped terraced cottages. Fairies was what they said, dancing in the old grey karn.1 Ill luck. Didn’t want anything to do with them.

Works had sprawled out from St Just since the 1800s, but it was only in 1862 that the Common raised an engine house high above the great fetch of raw Atlantic. Steam powered the Stamps that smashed the black ore, winding gear whined and spun to bring the men up from their service in hell. The miners heard knocking down in the dark, and left a pasty crust below. Topside, the dancing lights were another species of supernatural threat.

The land was flensed by industry, each valley a suppurating wound, each cliff top sentineled with belching stacks, even out onto Cape Cornwall where the waters meet. The furze was cut and fed into the flames, bright yellow blossom gone in a flash. Near 3,000 tons of tin were torn out of the ground, and at great cost to both land and men. The hissing sea drowned the submarine shafts, props collapsed, ladders broke, charges misfired. Death was a capricious yet constant presence.

In 1878 the thirty year old William Copeland Borlase strode across the despoiled land; a gentleman, a dreamer, the scion of an illustrious family, drawn by the miners’ tales. By now the site was buried under spoils, and he had grand plans to salvage it. William was the great great grandson of the folklorist Reverend William Borlase, and was raised in ‘The Iron Castle’, the Borlase family seat where antiquarians would meet to discuss the drolls and dolmen.

In West Cornwall it was commonly said that Borlases were in Cornwall before the birth of Christ, but the family were not originally of Cornish stock. As landed gentry, serving under James I and Elizabeth, their bloodline is charted back to 1066 and the Norman Taileffer family.2 They took their new surname from the Cornish Manor they were first granted, up near St Columb Major. Borlase is from the Cornish bor, the word used for a tumulus or burial mound, and glas for green or grey. The land there is speckled with them, from Winnard’s Perch up to St Breock Down, along with a rare stone row and the crowning quartz-crazed monoliths.

As the Borlase family moved west it was the ancient houses of the dead that became an obsession for them, spanning three generations. The Reverend grew to be one of the three great Cornish antiquarians, standing alongside Bottrell and Hunt.

As a teenager, precocious William Copeland had overseen the excavation of Carn Euny and its remarkable fogou. After finishing his stint at Trinity College, Oxford, he published the lavish Nænia Cornubiæ, in which he lamented the ‘heavy hand of ruin’ that turned the land inside out like a jacket. In the study he gave his motivation,

to preserve from oblivion, those records of a ‘speechless past’ which are daily falling prey to the pickaxe and the plough.

It is an exhaustive and important work, carefully recording sites across the county and reproducing elegant engravings. My copy, an hundred and fifty years old, library stamped by Dartington Hall, resold in Penzance, and though foxed still tight, accompanies my own journeys into the land. It is good to walk in company.

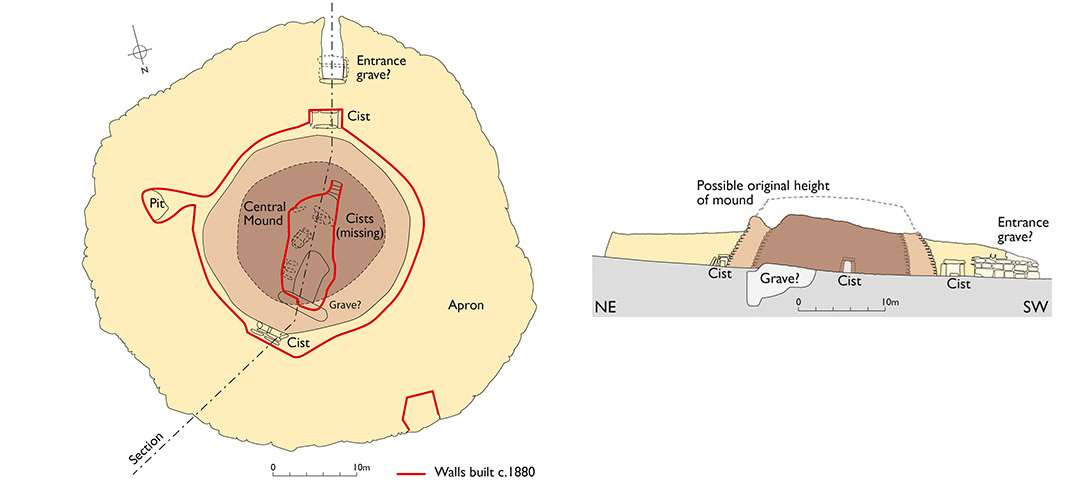

Under William’s direction the stone cockpit emerged, the dead cradled in their sockets, as packed black ash in rough red ribbon-handled pottery jars. His men rebuilt the walls at his instruction to better show the stone box kists of the great necropolis.3 Later archaeologists damn him for the work, but without Borlase and his ambition, the karn would have surely been lost forever to the wreckage of industry.4

The excavation revealed a chimeric structure, spanning thousands of years. Once it was a cairn towering fifteen feet high and sixty-five feet wide. The wheel-shaped barrow engulfs a late Neolithic entrance grave and an additional cluster of up to five middle Bronze Age kists. An entirely different people had moved onto a land littered with stone enigmas, and joined their own dead to a site already a thousand years old. And what of the treasures? A stone spindle whorl, some human and animal bones, pottery shards. A worn Roman coin slipped into one of the outer kists suggests even later use, or a gift to the dead and their waltzing lights. If there was more it had been long robbed.

For Borlase, things ultimately unravelled, bankrupting himself with lavish books, foreign travel and a Portuguese mistress who exposed his affairs and forced him to resign from Parliament in disgrace. His lifestyle and scandal destroyed the family fortune, with the Iron Castle sold to become a youth hostel.5 William died at fifty in London, estranged by his relatives, but part of him lives on as a ghost, walking the rounds of barrows and stones in far West Penwith. I am not sure we should consider that a curse, but his life of wandering suggests he was piskey led from young.

In 1883 the mine closed on Ballowall Common, five years after the barrow was excavated. The engine house was pullled down, the fine stone scavenged. The finger of the chimney was left to stand as a daymark for passing ships. Brambles and bracken roamed over the piles of broken stone.6 The work of Borlase and ancient man now basks by a ribbon of singletrack asphalt going nowhere, and is indicated by a heritage sign. On the seaward side the coast path reels oblivious pilgrims past on their way to Sennen, their eyes drawn by the sparkling water.

Autumn equinox is the day of the grasshopper’s last rasp, twinned butterflies orbit each other and the Stone Chats clack. Out in the tidal race wet kelp heads glitter. The moment that the light and dark year mix has drawn us to where the waters meet, Celtic Sea and Atlantic Ocean merging at the Cape. And I believe that the tomb builders witnessed this too, had found this place where the world ended, saw where the dead would go – out on the great golden boat of the sun, rowed by the silver oars of the moon. The entrance grave, long enough for a body to be laid, is oriented to what Borlase called the ‘death-quarter’ where the sun goes down. The flotilla of kists are lined up behind it. On this particular day a spider had spun her web across the entrance. We left her undisturbed.

There are no rites extant. Only the mystery of a stone spool which has seemingly wound back industrial time. The lights suggest the simplest honour is to process about the necropolis, as they do in Ireland, to be those small quiet feet. To dance. At other times it is best to leave it to the denizens of the mound, and on those nights we are not required for their magic. Sometimes you can bring them milk, honey, beer and light. Another offering is to write.

This equinox I am held like a prayerful seed in the cupped hands of the karn. The bees work around me, find the last sip of honey in the heather bells. The wind keens and whispers. The Stone Age sun sings into a procession of empty stone kists. And I am just another skull, jostling with the rest, late to my bed. The stone machine, piloted by the dead, commands the great gate. The seeds sleep, and in their sleeping dream.

The day passes with miracles, the complete flock of choughs in the parish, some seventy individuals, wheels over lilts, drifts and calls, and then a charm of goldfinch, thirty strong. The land, is casting off her coat of flowers and autumn’s bright light is pricked bloody with hawthorns.

Karn, Cornish for a heap of rocks, as in cairn. One name for the site is Karn Gluze, the grey cairn, another is Krug Karrekloos, grey stone mound.

The jester Taileffer purportedly struck the first blow at the Battle of Hastings, killing an English soldier who broke ranks to smite the mocking Norman.

Cist, pronounced with a hard ‘K’ as Kist, is a stone coffin or box; one of the few Cornish words that made it across into modern English with only a slight orthographic change.

Borlase noted another site with similar elements in the vicinity, and it is entirely lost, as are many of our ancient monuments.

https://www.yha.org.uk/hostel/yha-penzance

Compare this image with the black and white one reproduced above, the mine chimney in question is the one with the white band. My picture looks in the opposite direction.

Beautiful and evocative invitation to let our contemporary fingers trace the scars that the past has left in our landscapes and ourselves. Thank you

A captivating read, Peter — one we’ll no doubt return to. The wreckage of industry resonates deeply and remains all too prevalent. The kids and I often take a ‘trespassers’ pilgrimage’ to a local East Kent barrow hidden in private woodland. The mound contains burnt remains in upturned sepulchral urns (C. H. Woodruff). The trip has always carried that blend of excitement and exhilaration. But our last visit ended in devastation — logging machinery had gouged the mound and left the surroundings unrecognisable. We placed offerings. So much is lost to industrial farming and ignorance.