Getting into the Pisky business

Part seven: Lucky Charmers

Polperro fished through the flashing silver pilchards and then misled the excise men to land their other secret catch, ‘brandy for the parson and baccy for the clerk.’ That sense of a secret trade which arises from the needs of the people, and not the arbitrary rules of some distant parliament, is a vital part of the rebellious Cornish spirit. Mysterious lights moved through the night, secrets were kept and tunnels and caves lead down to an underworld richly stocked with treasure.

The isolated village changed forever when the charabancs started to run from the Railway Station at Looe and the motor car became popular. They brought tourist gold to funnel down the steep sun trap valley to the amateur museums, tea and souvenir shops selling smuggling, supernatural and superstitious Cornwall back to the emmets.1

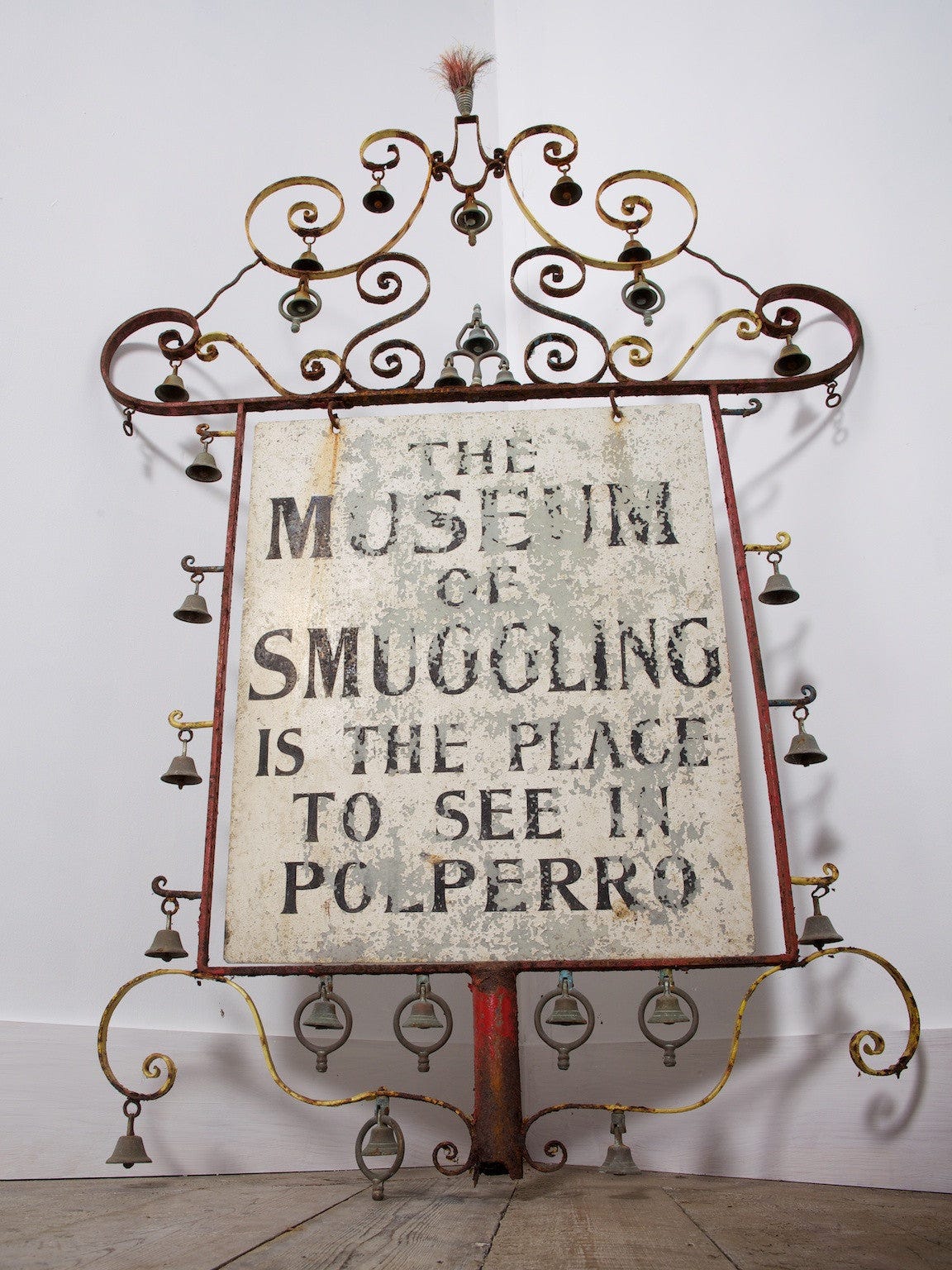

In those narrow streets a ten foot tall sign could be seen, proudly jingling an array of bells and bright tassles. The ingeniously wheeled lure, fabricated to order at the village forge, was rolled out to direct the shoal into the clammy basement which housed the Museum of Smuggling. They never stood a chance. Cecil Williamson, film director, spy and witch-master had come to town.

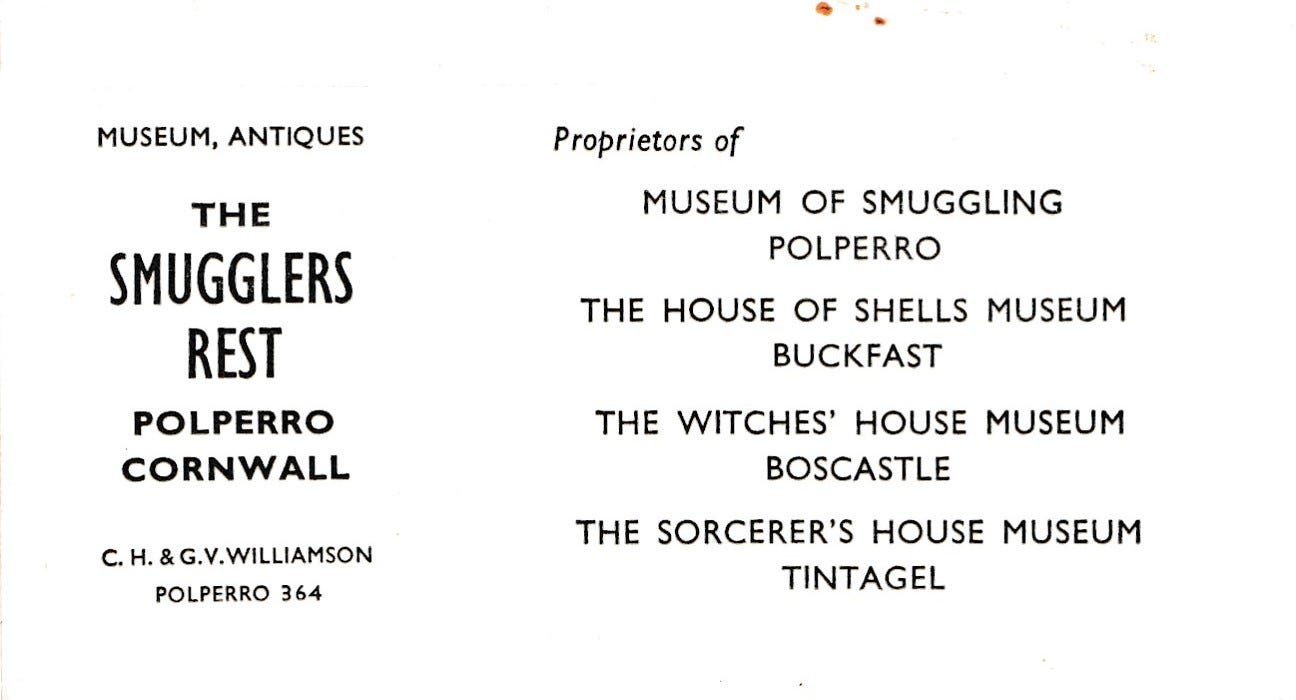

Williamson and his wife Gwen ran their West Country operations from the storied and eccentric village. It was a beautiful place to be as the hallow of the post-war dawned into the sixties, and far from the controversies of Bourton-on-the-Water. Cecil could head up over the granite moor to the north coast and supervise the Boscastle and Tintagel outposts, whilst Gwen with the skilled hands of a professional make-up artist deftly painted and stuck shells for the Buckfast museum.

Not mentioned on the 1960s business card, shown above, was the short lived House of Spells in nearby Looe which opened in 1959 on Lower Street. The business was passed over to William Paynter in that same year, becoming the Cornish Museum, and Cecil’s collection relocated to the Boscastle museum which opened in 1960.

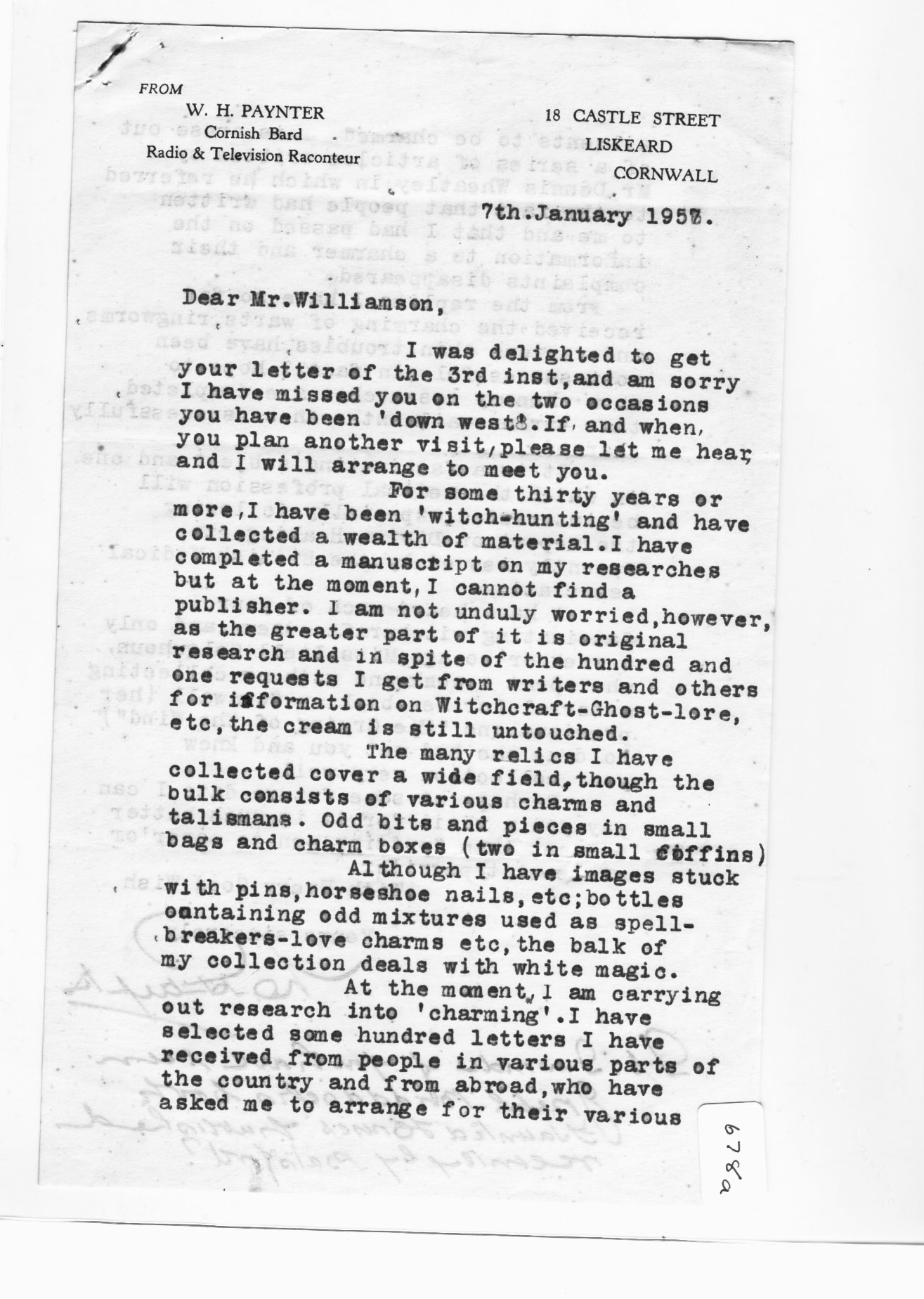

Bill had first made contact with Cecil on 7 Jan 1957, sending him a formal letter. His headed notepaper proclaims him:

Cornish Bard.

Radio and Television Raconteur.

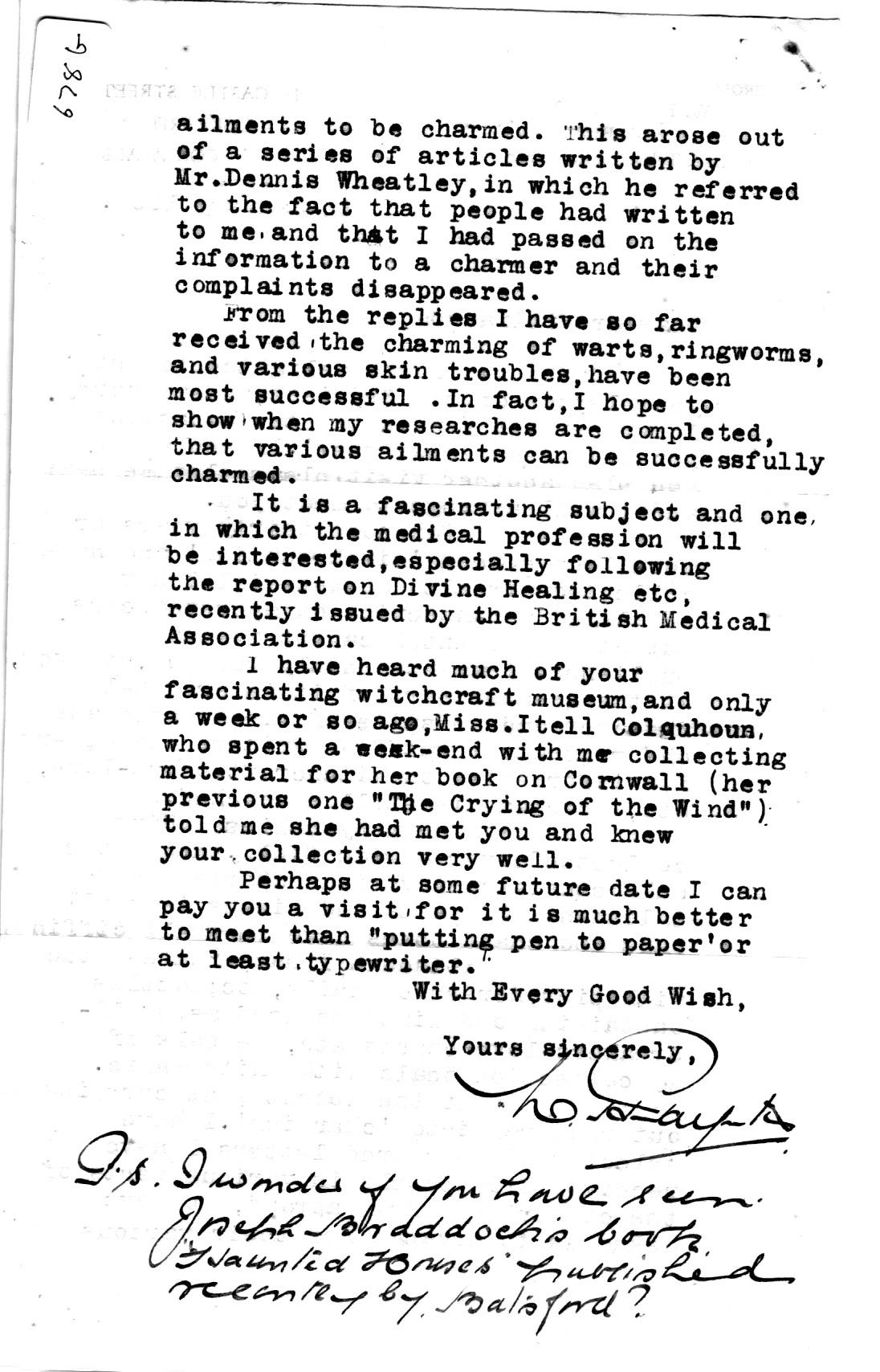

He sends another letter which gives a list of the talks he offers, but frustratingly there is no further record of their relationship beyond a couple of black and white snaps of the exterior of the Boscastle museum in Paynter’s effects. Bill had been collecting folklore in Cornwall since the 1920s, hence his Bardic name, Whyler Pystry – the Witch Finder – awarded in particular for his work in the Old Cornwall Society. How often the intelligencer and the raconteur sat and talked, comparing discoveries, contacts and stories is entirely lost to us. Or, if we are to consider the ways of the West Country pellars (the word Bill habitually used for an assortment of magical practitioners), who would never allow the spoken element of their charms to be written down, the lack of a record of what passed between the two men in itself preserves the magic.

Bill had quite the collection of charms: ash twigs, sheep teeth, moleskin, bones, stones and powders, some decanted into bags, boxes and miniature coffins. He had amassed other glories too, the Spanish scent bottle Helston wisewoman Tammy Blee used for mixing love potions,2 witches’ canes of twisted Nailsea glass, abracadabra charms and African fetishes. William Paynter was the successor of the earlier giants of Cornish folklore William Bottrell, Robert Hunt and Polperro’s own Thomas Quiller Couch, all of whom wrote in the late 1800s. Having failed to get his own work published outside of local newspapers, though appearing for a cameo in Ithell Colquhoun’s The Living Stones: Cornwall, Bill has only recently been properly acknowledged and his papers published.

Paynter sold dragon’s blood powder to cast on the fire for love magic, as well as metal charms of toads, hedgehogs and flying witches and most importantly of all, the Hap Da, a brass watch-fob charm of his own invention. The Hap Da (‘Good Luck’ in Cornish) bears a central pentagram figure on an escutcheon which is bisected by a vertical line to create the druidic Awen. Arrayed about it are a Celtic Cross, a Pilchard, an Engine House, a Chough and nearby Trethevy Quoit. The motto of the county – Onen Hag Oll (One and All) – rests below.

The collection of elements may seem idiosyncratic, but the charm is fit for purpose. The Hap Da is designed to protect both fishermen and miners (the most dangerous Cornish professions), and comprises Christian, Druidic and Arthurian symbols (the red-legged chough is the soul of Arthur). It is a product of the emergent Celtic Cornish nationalism of Henry Jenner and Robert Norton Vance, whose sky-blue acolytes were on the march with a renewed sense of identity. We can also recognise in it a revised version of the talismans once produced by the cunning folk, as well as a keepsake for the visiting tourist.

Paynter explains it thus:

A Piece of Cornish History. No 7. THE HAPDA. This charm, with signs of the Druids' preachings, is said to have special powers. The bards who were in charge and led people to believe in the powers of sun gods, still meet on the moors and carry on their ritual praying when the sun reaches a certain height and shines through on to a sacrificial stone.

Paynter is referring to Trethevy, perhaps the most remarkable, and certainly the most massive Cornish dolmen, which is distinguished by a hole in the capstone that aligns with the sun on the summer solstice and casts a dramatic pool of light.3 This area of East Cornwall was very much his stamping ground, close to the Hurlers stone circle where he had been initiated at the 1930 Gorssed, and the eccentric natural stacked granite of the Cheesewring where his ashes would ultimately be scattered.

Bill Paynter will have been aware of Cecil’s Tanat cult hypothesis, because in the slim crescent of time in 1959 spent at the House of Spells in Looe, Cecil had advertised his Tanat charm. Perhaps Ithell Colquhoun had quizzed Bill about the cult of Tanat too, as she consistently pressed Cecil for an introduction to them which was never forthcoming. If anyone could confirm or deny such a cult survival, it would have been Bill with his network of informants in the Old Cornwall Societies, whose motto remains ‘Gather the fragments that are left, that nothing be lost.’ The folklorists, antiquarians and amateur historians did exactly what they set out to do, and the shape of Cornish witchcraft, pellar and charming beliefs are now well understood, though Paynter was to lament a decade later that ‘Witch-belief in its traditional form appears to have gone forever.’4

Once again, there is nothing to substantiate the Tanat claims, and reluctantly we must consider that Cecil concocted the whole show. However, Paynter’s Hap Da charm and Williamson’s Tanat charm share a singular inspiration which ties them to both legend, place and custom.

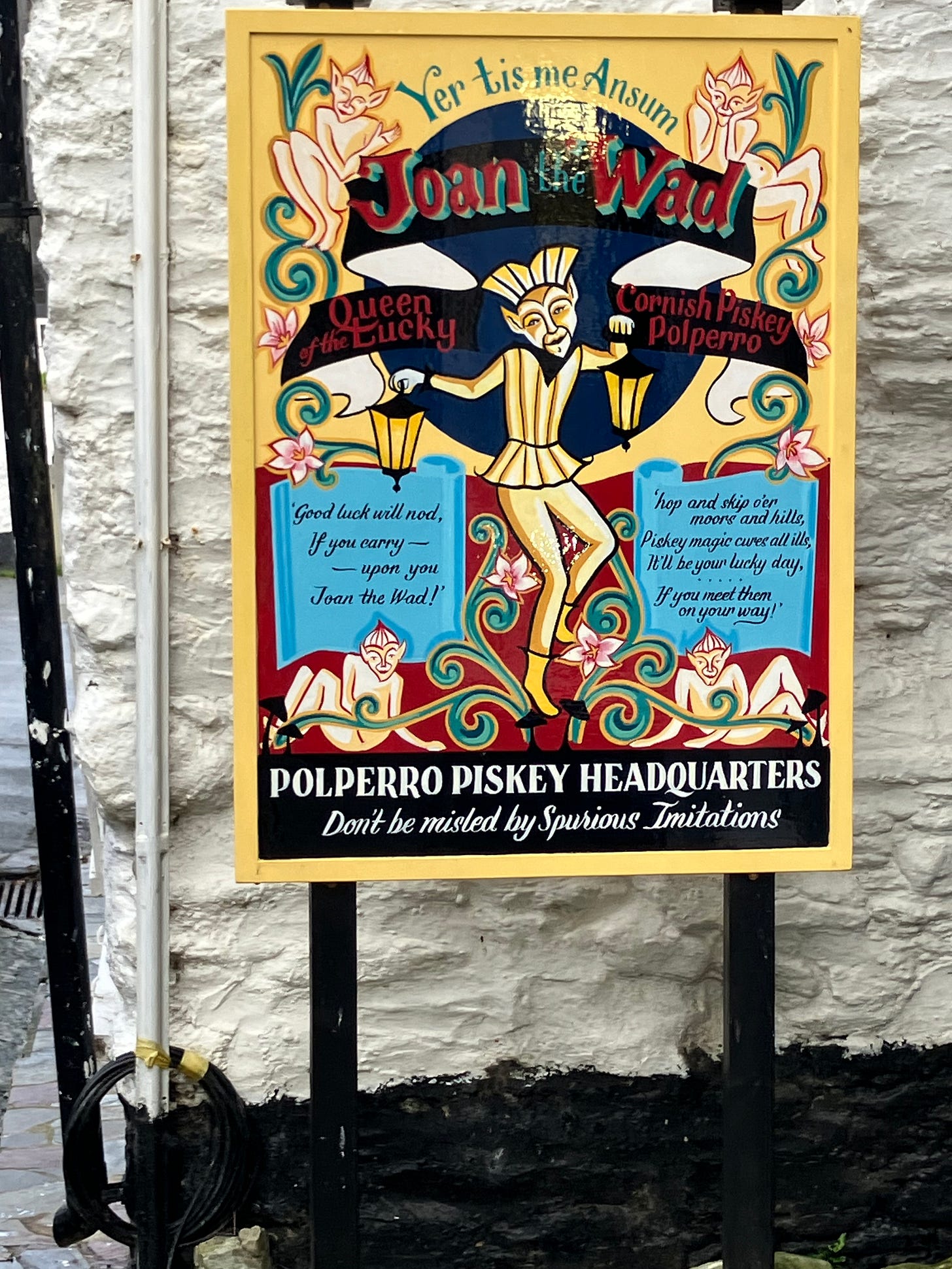

Polperro may have housed a Smuggling Museum, but the village kept another tradition alive, one that Cecil keenly observed, the pisky business. In the Joan the Wad shop, cast brass figures were sold in a brisk trade which was founded on the insistence that the Polperro Pisky was the greatest of luck bringers.

The English tourist has to return with a memento of their adventure, an item that speaks of supernatural and superstitious Cornwall. As a class of folk charm, the pisky fits. Whether you opt for Joan perched on a mushroom, or with an arm framing her head like a sailor’s pin-up, as a pendant to string, or perhaps a Jack O’ Lantern clad in a green shirt, red enamel boots and matching hat, there is luck to purchase in the form of fairy royalty. Some are crude and archaic, others look like liberty caps that have sprouted limbs to nimbly dance their rounds. The lantern of Jack and the wad (torch) of Joan are the otherwise inexplicable lights of the smugglers, the wandering will o’ the wisps rising from the wet earth, the orbs and spirits that congregate and hover over the geomantic power points. They are the ones who dance at the fairy and stone rings, or on the clifftops amongst the sea-pink gardens. They are the horse mane braiders, the unknown scythers, the ancient race, and yes, the child-stealers and deceivers who will lead one off the path. But in Polperro, Joan and Jack are specifically luck-bringers, with a dash of mischief and laughter.

In the accompanying pamphlets and adverts that spill from the pisky shop are modern stories of miraculous healing, lottery wins, marriages and protection for the ill-wisht. Behind them are an extensive series of encounters with the denizens of an older world, rolled smooth by the droll-tellers and hermetically sealed into individual plastic bags.

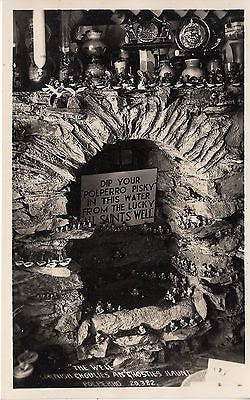

There were two specific claims for the authenticity of the charms: the first that they were the original, i.e. that Polperro was the pre-eminent site of pisky provenance, and the second that they had been dipped in what was variously referred to as the Holy, All Saints’ or Pisky well; baptised you might say, but into which Celtic faith there is some doubt. A replica well was installed in the shop so that visitors could perform the simple rite themselves and it was kept topped up with lucky water. A cynic might opine that the water likely came from the shop’s own lucky tap.

Cornwall is awash with wells, and they, along with the stones attract ongoing cult. However, not every well is a pisky well, and many have lost their spirits, or had them driven out. A pisky well was considered one that had a spirit before it had a saint, and they are not listed in the guidebooks. Once I thought that might have protected them, now I fear that without those stories attached to them, they will all be carelessly destroyed as farming, tourism and development encroaches.

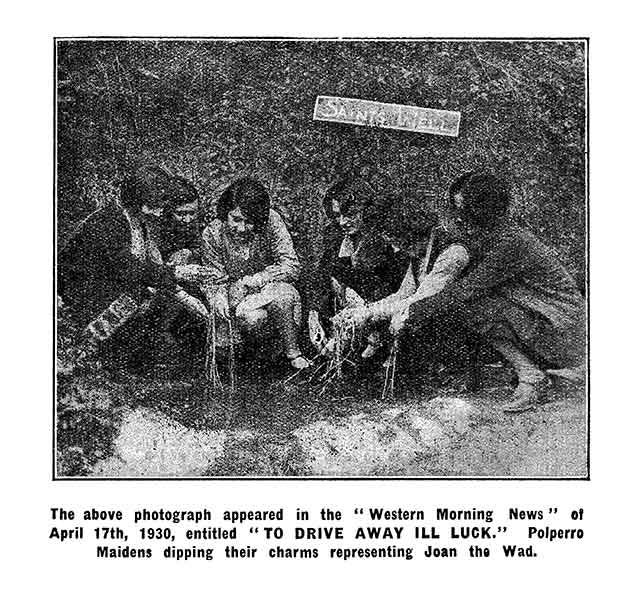

It is easy to dismiss as a stunt, but as late as 1930 Polperro maids were photographed dipping their Joans in the water of the Saints’ Well proper. It is a rite performed by women, allegedly to drive out ill luck, but no further details are given.

There is a vestige here of a Cornish folk tradition, with the baptising of dolls in similar manner found as far west as Newlyn where bent pins are offered to the well in thanks. The metal pin dates from the 1600s and before that the charm will have used a thorn. If a healing rite was needed, and most wells are sought out for healing purposes, the thorn would be one with which the sufferer was first pricked. Here I would kindly ask that you don’t go stripping thorns from any well guardian trees, they aren’t yours to take.

Though we might consider the inspiration as Catholic and dating to the Reformation, my intuition is that the rite of doll ‘baptism’ is a form of ritual behaviour that stretches back to the Paleolithic, as was the offering of a thorn or bone pin to a spring. I am not suggesting a continuous tradition or survival, but that humans engage in a ritual and magical relationship with place that arises directly from the land and the tutelage of its spirits. Polperro is a uniquely spirited fold in the land. The well was once connected to the medieval chapel of St Peter, and its water was used as an eye cure, yet certainly had a spirit before that which ‘Joan’ now stands for.

I believe that Polperro may have retained a genuinely archaic Cornish well tradition through a series of lucky accidents, culminating in the modern pisky business. So on a late October day we went in search of luck and blessing. Stashed in my satchel was an antique pisky door-knocker, sold to a shopkeeper in Penzance by travelling gypsies and now safely in our care.

Polperro is bedded in a moist, twisted valley that has preserved it from the modern world and brings a stream of tourists come to marvel at the jumble of cottages and shell bedecked houses, smuggling caves and souvenir shops. Everything is stuck with luck, peopled with peering faces. It has that sense of eccentricity, that spirit of place which selects for residents who have a peculiar character, and that must have been the case with Cecil. His smuggling museum is long gone, but its successor on the harbour has rescued and restored his original sign. It is the only trace of him the village retains.

Ducking off the main drag we wound up the steep lane which leads to the un-signposted and unloved well. There have been signs over the years, but none remain in 2024. It is situated in a no-mans land, forgotten by the town itself, described by well-hunters as ‘little more than a pothole’ by the side of a brutally climbing single track tarmac lane. The town may still have its visitors, but this sacred spot does not. The well is now an ivy hung wall that barely drips into a recessed basin of broken slates, even in autumn. Its source has been disrupted. It is enough for our baptism rite, but few, if any, are performed here these days. I am not sure even the proprietors of the pisky shop venture up here for holy water. There is no trace of maintenance, nor the small acts of care selflessly performed by those with a memory and reverence of the sacred. Polperro has likely forgotten the spot in less than a hundred years from when the six maidens were photographed dipping their charms into the waters for luck.

We perform our simple rite and head down to the town, watched all the while by spirits.

Cecil knew that the only business to be in was the pisky business. The baptised charm lodged in his imagination. What if his cult of Tanat had a not dissimilar rite for which he could claim antiquity? The House of Spells advertised just such a souvenir, and in his notes we find a series of rough drafts which reveal the method of preparation and the proper use of a ‘Pixie Charm’:

Lucky Pixies

The Cornish Gift Shops are full of them. Visitors delight to have one as a SOUVENIR

A reminder of a happy holiday.

But to be an EFFECTIVE LUCK BRINGER they must be charged with power and charmed by a person "Born to the Arts of Magic".

Such people still live and work in Cornwall.

Through them "THE HOUSE OF SPELLS" is able to offer its patrons a LIMITED number of "PIXIE LUCKY CHARMS". Which have been treated in a magical manner.

Amongst the many mystic procedures employed in the course of charming :----

Each Figure has been taken to the magic circle of TAN and charmed. (See photograph)

Each Figure has lain three days and nights beneath the waters of the moon pool of TANAT. (See photograph)

Each Figure is supplied FREE with the

TANATmagical "Square of Power" "& CONTEMPLATION". In itself a powerful Amulet and essential to the effective working of the charm.

THE PIXIE CHARM & YOU

NEVER LET IT FALL TO

THE GROUND ORTOUCH THE GROUND FOR THAT WILL BREAK THE GOOD LUCK SPELL.CARRY THE CHARM WITH YOU AS OFTEN AS YOU CAN.

AT NIGHT AND IN TIMES OF SPECIAL NEED PLACE THE CHARM IN THE CIRCLE PROVIDED FOR IT WITHIN "THE SQUARE OF POWER & CONTEMPLATION".

TAN. PRICE 3/- Each

TANAT. PRICE 3/- Each

THE SQUARE OF POWER AND CONTEMPLATION". FREE OF CHARGE. NO CHARGE.

The notes came as quite a surprise. I had assumed from the official printed application form that the charm Cecil was hawking out of the House of Spells was the square itself. I also followed Steve Patterson’s lead in believing there was a lost Moon Pool and a Circle of Tan charm, but that wasn’t true either. Cecil was selling piskies, or, to be more accurate, a story of how his piskies possessed magical power. If anyone was doing the charming, it was likely Cecil himself. Bill Paynter may have played about a bit with wart charming, but he never pretended to be a practitioner.

There were two actual charms, a Tan (Jack) and a Tanat (Joan), and as per the instructions they were worn as pendants and ‘charged’ when not in use by placing them on the square.

We cannot ever know the ‘many mystic procedures’ of Cecil, but perhaps we can discover where they were performed? The documents all say ‘see photograph’ yet those crucial images are missing. He is not using the well in Polperro, or the conveniently nearby white quartzite stone circle of Duloe. Sure enough, on another draft version of the Lucky Pixie document are found further details:

THE MAGIC CIRCLE OF TAN SOUTH WEST CORNWALL

THE MOON POOL OF TANAT MID. CORNWALL

Then there is a third document, in the disorder of notes, exhibit cards and objects held by the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic:

"Witchcraft in Cornwall"

Photographs of two lonely and out of the way places in Cornwall where acts of: ----

"witchcraft ritual" are till regularly performed: ----

Above The stone circle of "Tan" in which the "Dawn fire dance" is enacted.

Below The pool of "Tanat" on in and around which are performed "Rituals to the moon."

These rites are performed in the belief that they are the source of "magical power" used by the "Wicken" in their acts of “Witchcraft."

Again, the photographs are gone, as if the cult of Tanat had covered its tracks, sliding the evidence out of the mylar sleeves and spiriting them away.

We have to journey further into the landscape and the mindscape of Cecil if we are to make contact with his Tanat cult. Like the moon, we must climb the foreboding flank of the granite moor, follow the old road to Boscastle in search of the Moon Pool, and then head to the farthest south west to dance up the dawn in the circle of fire. The final secrets of the cult are yet to be revealed, but we are approaching the mystery.

To be continued.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Adder in the Churchyard Wall to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.