The cerulean blue of Mount’s Bay provokes a certain giddiness as it hoves into view. The fairytale castle amidst the sea, light sparkling on the water, adds to the realisation that this is not England; a truth that the Cornish hold as self-evident. There is a madness that comes with the brief glory of summer in the West, one which possesses visitors and locals alike. The incomers see the sails dancing in the breeze, encounter the circles and megaliths of Belerion and smell the coconut and surf wax scent of the furze grown from the acid dark pagan earth. Stories form as ozone drunk days end in beds sprinkled with Sennen’s white sand. At this latitude, with palms and succulents, fig trees and tamarisk stands, it seems an outpost of the Mediterranean. If a horse-prowed gaulos loaded with silver ingots of tin from that small island in the bay appeared, the dream would not be disturbed. And if those people traded with us for the magical metal that turned copper into bronze, they would have surely brought their gods, burned incense on the shore for their safe voyage or sunk votive statues into the warm clear waters. Others may have stayed. Cornish tin was reputedly used for the triple circled shield, pliant greaves and flashing helmet of swift-footed Achilles. King Solomon’s temple itself was equipped with tin from ding-dong mine. Legends to be sure, but tin has been worked here continuously for some 4000 years.

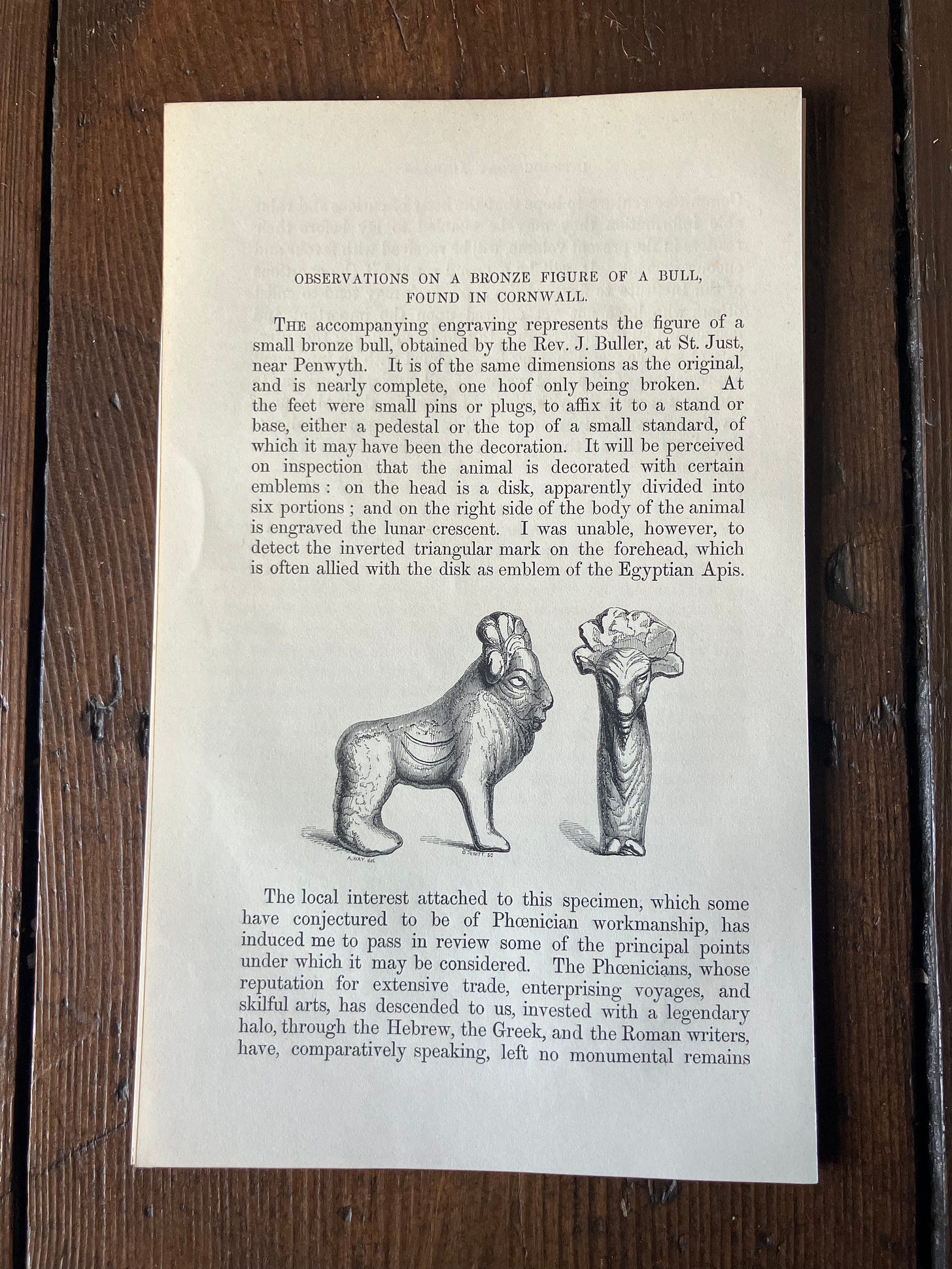

Already the historians will be turning a furious Tyrian purple, as well they should. Craig Weatherhill called the Phoenician hypothesis ‘one of Cornwall’s greatest fallacies.’ No recognised artefacts, trade goods or structures have been unearthed. The thumb length, tarnished bronze bull discovered at St Just with its hybrid human face and crescent cut flank is now reclassified as Egyptian, 747–332 BC, ‘probably dropped in Cornwall during the Roman period, AD 43–746,’ and thus an Apis rather than a Baal. It lies quietly in the Royal Cornwall Museum in Truro, no sense of its disputed provenance recorded, nor is there any mention of Phoenicia to be found in any of the displays. Fashions have changed.

The Greek and Roman historians started all the trouble. Herodotus spoke of the Tin Islands in the West, the Cassiterides, but the father of lies has little else to impart. The notion that these are the Scillies was dismissed as early as Strabo’s 7 BC Geographica, though that rumour persists in spite of the evidence. Cat skulls on the Scillies may support an Iron Age contact, but certainly no earlier. Tin mining did occur on the scattered archipelago, but the lodes were not significantly rich.

What we do have are accounts of the tin trade dating to 4 BC from the explorations of the Greek Pytheas who circumnavigated Britain, and whose lost Peritou Okeanu, is known to us from references by Timaeus, Posidonius, Pliny et al. The book itself perished with the library of Alexandria. However, Diodorus Siculus quotes extensively from Pytheas telling of the hospitable Cornish who cast astragali shaped ingots and took them to an island called Iktis at low tide from whence they were shipped to Gaul and then overland to the Rhone. It is a credible account of the ancient tin trade. Iktis must certainly be Michael’s Mount, given its proximity to the major sources of Cornish tin. The Hayle estuary once ran through from the North coast and disgorged into Mount’s Bay making Belerion itself a tidal island, and Iktis ideally placed for traders who could avoid the peril of Land’s End whether they came from Wales or Ireland in their shallow draft bull skin coracles.

Pytheas was proceeded by a Phoenician, Chimilkât, who made his own voyage in 6 BC, and receives the barest of mentions in Pliny’s Natural History. That navigator must have edged around Iberia and tacked up to Brittany before making the short crossing over to Cornwall. Though the Phoenicians were exceptional seafarers, it seems most likely that they would have been recipients of a trade run by the early Cornish and their colonies in Brittany and Galicia. Though that does not discount visits from navigators, miners, religious and trade delegations, a steady stream of contact is not necessary or substantiated.

Yet there are now physical proofs that the Atlantic tin trade stretched back much further. Ingots were recovered from a shipwreck in Haifa inscribed with the undeciphered Cypro-Minoan script. The wreck dates from the 13th–12th century BC and the tin, fingerprinted by isotope analysis, can only have been streamed from our local Carnmenellis granite. Perhaps the Haifa shipwreck makes the legend that Cornish tin was used in the Temple of Solomon, fetched by envoys of Hiram of Tyre, somewhat less fanciful than it first appears. What the ingots do prove is a late Bronze Age tin trade stretching from Cornwall to the Levant.

It was John Twynne (or Twyne) of Canterbury, a schoolmaster and antiquary whose 1590 De Rebus Albionicis, Britannicis, atque Anglis Commentariorum libri duo launched the Phoenician mania on the wind. Knowing that they had reached Spain he asks with the rhetorical flourish now beloved of alternative historians,

‘…my friends, did it not occur to the mind that this also once happened to Britain because of the fortunate metallic nature with which Cornubia, which is commonly called Cornwallia, abounds?’

Aylett Sammes upped the ante with his 1676 Britannia Antiqua Illustrata, or the Antiquities of Ancient Britain derived from the Phœnicians. He built on the Frenchman Samuel Bochart’s 1646 Geographica Sacra, which argued that the British Isles had been settled by the Phoenicians who gave us our language. Sammes confidently states,

‘I hope that in the following discourse I have plainly made out that not only the name of Britain itself, but of most places therein of Ancient denomination are purely derived from the Phoenician tongue, and that the language itself for the most part, as well as the customs, religions, idols, offices, dignities of the Ancient Britons are all clearly Phoenician…’

Sammes uses the same sources modern historians inevitably cite, but allies them with the certainty of biblical truth and the kind of unsteady etymologies and false friends which plagued the period. The work includes the atmospheric woodcuts of druids and wicker men that still haunt the English imaginal. What we have perhaps forgotten is his insistence that these wicker figures were made in memory of Phoenician ships, and that the darkly aspected Druids were for him the degenerate successors of the original Phoenician Bards. Even the many Cornish giant stories are conveniently dressed with a Phoenician etiology and the Phoenician Hercules is given prominence as a character.

If Sammes is largely forgotten, the antiquarian William Stuckeley is better known, mainly as an influence on William Blake. His pioneering antiquarian fieldwork resulted in a series of texts in the 1740s that proposed the Druids were a Phoenician colony led by the Tyrian Hercules, who built not only Stonehenge and Avebury but Boscawen-Un, perhaps the prettiest stone circle in West Cornwall. In his imagination the Druids had transmogrified into Trinitarians who having been here since after the Flood, anticipated Christianity and awaited a messiah. Thus England was the seat of the true religion, a theme which would be allied with the extant tales of Joseph of Arimathea and reach its pinnacle in Blake’s Jerusalem.

The fall into unsteady Phoenician etymologies continued with works such as Marcus Keane’s 1867 The Towers and Temples of Ancient Ireland, and Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1898 (writing as Sherlock Holmes) A Study of the Chaldean roots of the Ancient Cornish Language. The good doctor is clearly suffering from the intoxication with which I opened my essay, as he holidays in Poldhu and jaunts about the county as midsummer approaches and seems increasingly sun-struck. He quotes approvingly from Smith’s Bible Dictionary that,

‘The worship of Baal and Ashtoreth was supposed to have been common throughout the British Islands […] various superstitious observances obtained which either had reference to or closely resembled the worship of the Phoenicians.’

He found evidence of these in the testimony of one Reverend Roundhay, the vicar of Preddanick, who recounted being passed through a split ash tree as a sickly child and which Doyle interprets as an Asherah rite. The holed stone of Mên an Tol is still used in like manner for healing. The reverend then took him to witness ‘the crying of the neck’ where the last sheave of corn is cut and flourished to a call and response,

‘What ‘ave ee? What ‘ave ee? What ‘ave ee?’

‘A neck! A neck! A neck!’

Libated with cider and shouted out in broad Cornish, the words blur still further. For Doyle ‘neck’ became ‘nach’ a truncation of the Phoenician nachash, the serpent. Conan Doyle fancied himself transported to an ancient rite which is still performed, appropriately enough, on the Lizard. On Midsummer Eve he headed over to Belerion and the crowning event of his stay. At the summit of Chapel Carn Brea he witnessed a white clad maiden throw herbs into a blazing beacon, the event sanctified by a brief prayer from the local clergy; though as he observes, ‘it is only too apparent that the whole affair is a pagan one.’ The sun slowly descended into the waiting waters, and the Scilly Isles glimmered metallic beyond the sweeping light of Wolf Rock. Under his fictional monicker the events were carefully set down and the ancient authorities cited. The case is considered solved.

It was on the autumn equinox 1928 at Boscawen-Un that the modern Druids would hold their first solemn Cornish Gorsedd, dressed in fetching new sky blue robes. Horns were blown to the quarters, flower girls danced and Excalibur flourished in the name of immortal Arthur, now transubstantiated into a chough. The proceedings were conducted in the revived Cornish language and a mish mash of Christianity and Celticism. These rites of nationhood relied on the concocted Phoenician origins of Stuckeley and the Bards of Sammes. Cornish druidry washed the gore from the Roman accounts, and that of writers such as Borlase, to create an eccentric hybrid of Holy Land and native holy men.

The unlikely wedding of Christianity and Druidry is a mythic fudge that the Earth Mysteries current perpetuated. Old Etonian John Michell, whose 1969 The View Over Atlantis is canonical for Avalonians, was inevitably drawn to West Cornwall as the terminus of the Saint Michael’s Line. In his 1974 The Old Stones of Land’s End he states that,

‘the Phoenicians and Greeks sailed to Mount’s Bay to trade for metal, and through those channels went another trade between their philosophers and the British Druids, the last keepers in England of the hermetic tradition.’

Cornwall manifests myth. Just as the geomantic ley lines conjured UFOs for Michell and the counterculture, the veins of casserite ore pulled the Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans to our ancient Druid rocky shore. Left with the mysterious circles of the Bronze Age, the remnants of megalithic culture and fragmentary accounts from early historians, antiquarians, folklorists and nationalists composed a resonant story. Britain could rightfully become the New Jerusalem with archbishops and monarchs dressing in Druid robes. As one part pure tin can transform nine parts of copper into enduring bronze, one part truth can transform nine parts conjecture into an enduring myth.

With that stated, the second part of my droll will go on to tell of the sea witches and the Cult of Tanit herself.

Fabulous stuff. Trade routes were surely as much fertile channels of exchange for ideas, politics, skills, deities, magicks, people, sciences, knowledge, theologies etc etc as goods. If not the Phoenicians, then certainly the Greeks, Romans, Etruscans, Persians, Thracians etc. Maybe culture didn't weedle its way into Cornish hearts in the way Conan Doyle imagined it, but I wouldn't be surprised if ancient 'Cornwall' was far less insular than I / we think

Very much anticipating part 2. I'm now working on a short bit about the caves at Grotte di Capelvenere - one of the many sites dedicated to the cult of Tanit in Sicily...